- Home

- Stephen Kirk

Scribblers

Scribblers Read online

In the small mountain city of Asheville, North Carolina, Thomas Wolfe lies at eternal rest just a few steps from William Sydney Porter, better known as O. Henry. Those graves are a short hop from the great inn where F.Scott Fitzgerald tried to dictate his writing from the estate where the aged Carl Sandburg wrote deep into the night.

The city’s ties to the world of letters are equally strong today. Gail Godwin and Charles Frazier were schooled in Asheviile, for example, and Robert Morgan and Fred Chappell in the immadiate area.

Stephen Kirk, author of Scribblers, in the editor and would-be literary gadfly. Taking Asheville as has canvas, he learns stories of the area's legendary authors and interviews some of its contemporary greats. Meanwhile, he also seeks out writes living in the shadows of the famous. He meets genre authors who make their living penning romances, Weserns, and mysteries. He immerses himself in the culture of writers’ groups and conferences, exploring the hopes and frustration of the unpublished and self-published. For every well-known author, there are a thousand folks laboring in obscurity. What drives them so hard, given such a remote likelihood of success?

Scribblers is ultimately a humorous, sympathetic examination of the writer’s urge, set against the background of a noted literary town. Its Woody Allenstyle narrator, who wants to be in the club as badly as the rest, casts a critical eye on his own efforts as he flubs a few interviews, commits a faux pas here and there, and graually finds his way.

Scribblers

Stalking the Authors of Appalachia

Copyright © 2004 by Stephen Kirk

All rights reserved under

International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines

for permanence and durability of the Committee on

Production Guidelines for Book Longevity

of the Council on Library Resources

Design by Debra Long Hampton

Cover image by Martin Tucker and Anne Waters

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kirk, Stephen, 1960-

Scribblers : stalking the authors of Appalachia / by Stephen Kirk.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-89587-307-9 (alk. paper)

1. American literature—North Carolina—Asheville Region—History and criticism. 2. American literature—Appalachian Region, Southern—History and criticism. 3. Authors, American—Homes and haunts—North Carolina—Asheville Region. 4. Authors, American—Homes and haunts—Appalachian Region, Southern. 5. Appalachian Region, Southern—Intellectual life. 6. Appalachian Region, Southern—In literature. 7. Asheville Region (N.C.)—Intellectual life. 8. Asheville Region (N.C.)—In literature. I. Title.

PS266.N8K57 2004

810.9’975688—dc22

2004016038

For M, Z, and B

Contents

Chapter 1 Pencilneck’s Holiday

Chapter 2 Authors Anonymous

Chapter 3 Big Game

Chapter 4 Toil

Chapter 5 Critiquing the Critiquer

Chapter 6 Cornucopia

Chapter 7 Night Sweats/Self-Gratification

Chapter 8 Ham-and-Eggers

Chapter 9 Son of Bullitt

Chapter 10 Girl Power

Chapter 11 The Worthies’ Parade

Chapter 12 Unfinished Business

Acknowledgments

“Writers, like teeth, are divided into incisors and grinders.”

Walter Bagehot

CHAPTER 1

Pencilneck’s Holiday

The dancing Maxwell Perkins is too old for the part: that’s my first impression. The legendary Scribner’s editor was in his forties when he met Thomas Wolfe. This guy looks a good fifteen years older.

I’m attending a ballet based on Wolfe’s life. Called A Stone, A Leaf, A Door, it’s billed as a “world premiere.” Two of the girls in the chamber choir have barbwire tattoos around their ankles. Stage right, a solemn-looking fellow gravely intones poetry adapted from Wolfe while the dancers emote. A stone, a leaf, and a door are the dominant symbols in Look Homeward, Angel. I recently finished that novel and was hammered by those images for five hundred and twenty-two pages. Confronting them again makes my head hurt. Damn me for a lowbrow, but ballet seems a silly way to tell the story. I wish I had my ten dollars back.

I’ve come to Asheville, North Carolina, for the Thomas Wolfe Festival. Because of obligations at work, I was late getting on the road for the three-hour drive to this mountain city. As a result, I’ve missed the mock debates on the front porch of the Thomas Wolfe Memorial, the walking tour of Wolfe’s Asheville, the readers’ theater presentation of Wolfe’s story “The Child by Tiger,” the radio broadcast from the memorial, and Wolfe’s posthumous birthday cake. I’ve missed the presentation of sundry papers—“Thomas Wolfe: A Psychobiography,” “Thomas Wolfe and Aline Bernstein,” “The Flood of 1916 and Thomas Wolfe’s Antaeus, or a Memory of Earth,” “Thomas Wolfe’s Literary Use of the Civil War.” Maybe that’s for the best. To be honest, I’m not much interested anyway. And I’m too lame for the Thomas Wolfe 8K Road Race.

I don’t feel much affinity for Wolfe. He was a drunk, a skirt chaser, a mama’s boy, and a lout. He was needy, crude, self-pitying, and impressed with his brilliance. I admire him for his grand, naive ambition to capture the entire world on paper, but I don’t much care for his writing. When I began Look Homeward, Angel, the book so frustrated me that I started counting all the exclamation points and penciling a running tally at the end of each chapter. “O waste of loss, in the hot mazes, lost, among bright stars on this most weary unbright cylinder, lost!” O juvenile crap! Like many readers before me, I later got caught up in the high madness of his thinly fictionalized family. But the novel ultimately seemed as overstated as the man himself.

Asheville impresses me as much as Thomas Wolfe doesn’t. The city lies at an elevation of twenty-five hundred feet in a protected bowl of the southern Appalachians between the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east and the Great Smokies to the west. It occupies a temperate zone in which rain is more plentiful but the air is generally drier, in which the summers are cooler and the winters milder, than in the areas east and west of the mountains.

The corridor of the French Broad River first became a haven for people of means in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, when South Carolina planters seeking to escape the heat and yellow fever of the coastal lowlands built grand homes at Flat Rock, just over the North Carolina border. Meanwhile, another wealthy enclave developed at Hot Springs, fifty miles north-northwest, toward the Tennessee line. Midway between the two was Asheville, which attained a fame as “America’s Magic Mountain” as the privileged escaped to its healthful climate and spectacular views.

Foremost among the Northern bluebloods who came to town was George Washington Vanderbilt, who visited with his mother in 1887. Local legend has it that Vanderbilt was on the south veranda of the Battery Park Hotel when he saw the vista of rolling mountains that inspired him to create the Biltmore Estate. Encompassing a 125,000-acre tract of forest, a 250-room chateau, and a complete support village, it was a private domain unequaled in America. Twenty-six when he began acquiring local property and thirty-three—and still a bachelor—when the chateau was completed in 1895, Vanderbilt never considered that he might have overbuilt, or that Asheville was a backwater, the railroad not having reached town until 1880. He believed that if he did things on a grand-enough scale, the world would come to him.

Aside from its beauty and climate, the area had little to recommend it. Most people were small farmers on difficult ground; they were self-sufficient but cash-strapped. The influx of wealth into what had long been a hardscrabble region brought jobs. It also furthered the tradition by which

the best assets of poor places are owned by interlopers.

The juxtaposition of plenty and little was one of the factors that gave rise to a surprisingly rich writing tradition centered on a city that only recently topped fifty thousand inhabitants. Some say literacy came late here, but a rich vein of material awaited those who picked up a pen. Thomas Wolfe is Asheville’s favorite son. O. Henry once had an office downtown. F. Scott Fitzgerald spent a couple of summers at the Grove Park Inn; Zelda died in an asylum fire in Asheville; Tennessee Williams organized one of his late, failed plays around that fire. Walker Percy summered for many years at nearby Highlands, where he conceived the idea for The Second Coming, set in Asheville. Gail Godwin spent her formative years in Asheville’s Catholic schools. Charles Frazier was educated here, too; his Cold Mountain lies forty miles west. John Ehle is from West Asheville.

Draw a circle with a radius of thirty miles around the city and you take in these writers: Carl Sandburg lived out his later years in Flat Rock; Fred Chappell is from Haywood County, west of the city; Robert Morgan grew up in Henderson County, to the south; Tony Earley is from Rutherfordton, to the southeast; Lilian Jackson Braun lives half the year at Tryon, to the south; Patricia Cornwell spent part of her youth at Montreat, to the east, where she was mentored by Ruth Bell Graham, the wife of Billy Graham. The Black Mountain College writers inhabited a strange, culturally significant little campus near Montreat.

Residing under this noble forest canopy is an under-story of genre authors and writers of regional or minor national note.

Beneath that is a ground cover of writers’ organizations, critique clubs, and literary retreats—the Writers’ Workshop, the Asheville Plotters, the Hendersonville Writers Support Group, the Writers’ Guild of Western North Carolina, the Transylvania Writers’ Alliance, the Burke County Cross Country Wordsmiths, the Cashiers Writers’ Group, Mountain Voices, numerous splinter groups, and, no doubt, others unknown to me.

I’ve traveled here to glean insights from the lives of famous authors in a town with a rich literary tradition. But more than that, I want to examine the writer’s urge as manifested in flesh-and-blood scribblers, whether they be great or humble, successful or failed, recognized or frustrated. From the unknown among them, I want to learn what compels people to daily confront the limits of imagination, to continue nursing hopes when the possibility of real success is so slim. I’d like to know why writers think they can take their mostly mundane experiences and ideas and create something of value.

The final event of the Thomas Wolfe Festival is the dedication of the new visitor center at the Wolfe memorial. That facility, located behind the memorial proper—the boardinghouse known as the Old Kentucky Home in Wolfe’s day and immortalized as Dixieland in Look Homeward, Angel— contains restrooms, display space, a gift shop, and an auditorium. It’s also designed to save wear and tear on the old boardinghouse itself.

I gather with perhaps a hundred others on the memorial’s back lawn for the ceremony. In the crowd with me is Wilma Dykeman, author of The Tall Woman and grande dame of Appalachian literature. Among the speakers is Dr. Dietz Wolfe, a descendant of one of Thomas Wolfe’s brothers. But most everyone, I suspect, has come to hear Pat Conroy.

Spiritual heir of Thomas Wolfe, Conroy shares Wolfe’s verbosity and exuberance. Conroy’s writing, too, has been known to ride roughshod over the family of his youth.

Ruddy, heavyset, blocklike, his hair gone nearly white, Conroy speaks of his passion for Thomas Wolfe’s writing. He tells of the day when, an impressionable South Carolina high schooler, he came with his English teacher to the Thomas Wolfe Memorial. His teacher took him to the backyard where we now stand and made him eat an apple from a tree here, figuratively planting the seed of Conroy’s own literary career. He has made numerous pilgrimages to Asheville since. Within the past year, he has traveled to town to write a screenplay of Look Homeward, Angel.

Well prepared, comfortable in front of his listeners, Conroy calls up his emotions with ease and grace.

As the gathering breaks up, I’d like to make my way to the front to meet him.

“Mr. Conroy, your speech meant a lot to me,” I could say.

I’m sure he’s never heard that one.

Or “I love your books.”

That’s not exactly true. I’ve read only a couple, and so long ago that I’m not sure what opinion I’d hold of them today.

Or “Mr. Conroy, I have some reservations about Thomas Wolfe—and his admirers.”

That would be honest, but a bad idea nonetheless, and certainly inappropriate to the occasion.

Or I could simply introduce myself.

I’m sure he’d be honored.

So I skulk away without saying anything to anyone.

The Tapestry Gallery in Biltmore House contains the estate’s principal portraits. The John Singer Sargent painting of the man of the house stands out among Vanderbilt portraits because of one object in prominent view: the book in George Washington Vanderbilt’s hand, held delicately at his shoulder.

The Vanderbilts were hardly bookish. George was the first intellectual in four generations of America’s most acquisitive family. He began collecting books and art at age eleven and eventually amassed twenty-three thousand volumes and learned to read eight languages. His Biltmore library was a source of particular pride. The sixty-four-by-thirty-two-foot Pellegrini painting on its ceiling, disassembled from a palace in Venice, testifies to the room’s size. The library holds first-class collections of history, horticulture, travel, and foreign-language titles and nineteenth-century English and American literature.

Moreover, George Vanderbilt had writerly aspirations himself. In his private study at Biltmore, which he called his “scriptorium” he penned first-person hunting adventure stories that cast him as a dashing figure in the Teddy Roosevelt mold. A couple of those stories still languish, unpublished, in a private archive.

Vanderbilt liked to host famous authors for extended stays at Biltmore.

His unhappiest guest was Henry James, then as now ignored by American readers. James came in February 1905 during his return to the United States after twenty-one years in Europe. Suffering gout, carpal tunnel syndrome that made the act of writing painful, and the aftereffects of a forty-day course of dental work, James grumbled in his correspondence that Vanderbilt’s “strange, colossal heartbreaking house” was “a gorgeous practical joke.”

But Edith Wharton, who arrived for the Christmas holiday that same year fresh off the publication of her breakthrough novel, The House of Mirth, loved the place.

One guest who is obscure today but may have cast a longer shadow than either James or Wharton in his own time was Paul Leicester Ford. In his scant thirty-seven years, Ford established a national reputation as a printer, historian, biographer, bibliographer, and novelist. His 1899 novel, Janice Meredith: A Story of the American Revolution, sold two hundred thousand copies in its first three months, a record to that date. One critic christened it “the great New Jersey novel,” no irony intended. It spawned the Janice Meredith Waltz and a hairstyle, the “Meredith curl.” The first text inside the front cover, it so happens, is a slavish page-long dedication to George Vanderbilt. “My dear George,” it goes in part, “As I have read the proofs of this book I have found more than once that the pages have faded out of sight and in their stead I have seen Mount Pisgah and the French Broad River, or the ramp and terrace of Biltmore House.… With the visions, too, has come a recurrence to our long talks, our work among the books, our games of chess, our cups of tea, our walks, our rides, and our drives.”

I saw Biltmore from the air some years ago, when I visited Asheville for a previous employer. Ignorant of where the estate lay in relation to the airport but knowing it was out there somewhere, my fellow passengers and I searched for it out the right side of the cabin as that wing lowered briefly during the climb, then swung our heads left as the aircraft banked the opposite way. Everyone let out a collective “Ah”—there it was, clo

ser than I’d hoped, right where I might have landed at the front door had I rolled out the plane’s window. It remains one of the most spectacular sights of my life.

Arriving by air is the best introduction to Asheville. Following wave upon wave of rolling green mountains, the bright downtown is a revelation. So striking is its architecture that on the heels of the city’s christening as “America’s Magic Mountain” came a nickname even more hifalutin: “the Paris of the South.” That’s too grand by a factor of twenty, but the point is taken. Instead of defaulting on its loans after the stock-market crash of 1929, Asheville made good on every cent, which meant it was still paying its Depression debt as late as 1976. The positive side of this was that the city lacked the funds or the will to remake its downtown during the urban-renewal boom. When good times returned to the area, the architectural gems of the Roaring Twenties were waiting to be dusted off.

To try to re-create my first experience of the mountains, I’ve booked a private tour flight. At a cost of a hundred and thirty dollars for an hour’s time, it’s an extravagance I can’t justify. I tell myself it will clarify my purpose and give me perspective.

The office of the flight school lies at the end of a long hall in an outbuilding at Asheville’s airport. One of the two men working there introduces himself as Billy and asks me what it is, exactly, I’ve come to see. I was vague over the phone.

“Well, is the person who’ll be taking me up pretty familiar with the area? Geographically, I mean.”

“All our instructors are.”

“And he’ll show me whatever I ask?”

“As far as he can.”

I tell him I want to see Asheville proper, but also Oteen, Canton, Cold Mountain, Tryon, Hendersonville, Flat Rock, Black Mountain, Montreat, and maybe as far north as Mount Mitchell and Burnsville.

Billy takes a quick glance at his coworker. “Um, you know your hour begins as soon as the propeller starts spinning. By the time you’re cleared for takeoff, then have to taxi back to the building afterwards, that’s a significant amount of time right there.”

Scribblers

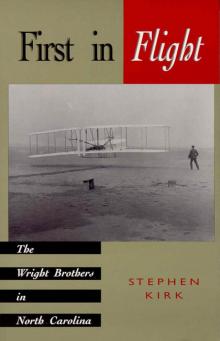

Scribblers First in Flight

First in Flight