- Home

- Stephen Kirk

First in Flight Page 2

First in Flight Read online

Page 2

It was at an 1886 conference Chanute helped organize that Samuel Langley had his first formal contact with the aeronautical community. Initially, both men were hesitant to let their interest in the subject become public knowledge. Chanute revealed his passion for flight only to his aeronautical correspondents and a few friends. Langley conducted his early experiments in aerodynamics behind a fence and referred to them as his “work in pneumatics.” They both had reputations to protect. Aligning themselves with the long tradition of cranks who wanted to fly could only expose them to ridicule.

Born in 1834, Samuel Langley was one of the country’s foremost astronomers. He was best known for his study of sun spots and his measurement of the heat generated by the sun.

As a scientist, Langley approached aeronautics in a different way from Octave Chanute. Rather than surveying what had previously been done in the field, he set about designing experiments to determine how much horsepower would be needed to sustain a wing in the air. Toward that end, he built what he called a “whirling table”—a long, horizontal arm mounted on a vertical pole and driven by a steam engine. When the “table” was turning at top speed, the tips of the arm attained speeds of nearly seventy miles an hour.

Langley mounted a variety of measuring instruments, wing surfaces, and stuffed birds—a buzzard, a California condor, an albatross—on the arm and set it to spinning. When his results were in, he concluded that flight was not only attainable, but that as speed increased, less and less horsepower would be needed to sustain a craft in the air. Further study into the nature of wind action led him to envision a day when airliners would be able to circle the globe, firing their engines only during times when there was no wind.

The scientific community scoffed at such notions. Langley saw that his only chance to make his ideas more palatable was to build a workable flying model.

He began tinkering with models as early as 1887, but his real work in aeronautics began in 1891. By then, Langley had been chosen secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, the highest position at the national museum. As such, he had considerable resources at his disposal, and the backstage areas at the museum were gradually transformed into aeronautical workshops. Langley served as chief designer and administrator for the project, doing none of the actual building himself.

He called his large-scale models “Aerodromes.” The staff at the Smithsonian built a total of seven, the largest weighing thirty pounds and boasting a wingspan of nearly thirteen feet. Langley favored a tandem-wing design, with one set of wings behind and in the same geometric plane as the other—like a dragonfly—and the steam engine that drove the propellers between the forward and rear wings. The launching system consisted of a twenty-foot catapult mounted on top of a houseboat floating on the Potomac River. Langley thought such a system would allow the Aerodromes a slight loss of altitude until they attained flying speed. Landing in water would also minimize damage to the craft.

The year 1896 marked the high point of aeronautics before the Wright brothers. After five years of buckling wings, faulty launches, engine troubles, and staff turnover, Langley and his assistants brought two of the Aerodromes to the houseboat on the Potomac for testing on May 6. With the great Alexander Graham Bell as a witness, the first craft sheared off a wing on launching, but the second made an astounding flight of over half a mile. After it was retrieved and allowed to dry, it was launched again and flew nearly as far. Another test was conducted in late November, one of the Aerodromes covering forty-two hundred feet at a speed of thirty miles per hour.

Samuel Langley’s views on flight and his principles of aeronautical design appeared to have been vindicated, and he set his sights on building a full-scale Aerodrome that could carry human passengers.

Meanwhile, Octave Chanute was also enjoying a remarkable year. After nearly two decades of studying the flight problem, trading ideas with many of the world’s top aeronauts, and inspiring numerous young men to take to the air, he was finally ready to apply his experience toward building a glider.

His master design was for a “multiplane” craft with a maximum of sixteen wings, eight of which could be stacked on either side of the fuselage. Chanute’s plan allowed for the wings to be stacked either at the front or back of the craft in a variety of configurations, nearly all of which were tried: four wings in front and eight in back; two in front and eight in back; twelve in front; two in front and ten in back; and eight in front and four in back, which proved to be the best arrangement. Each of the six-foot wings was mounted on a spring that allowed it to rotate slightly in a gust of wind, giving the glider a measure of stability. With a nod to its insectlike appearance, the craft was called the Katydid.

Chanute’s second glider, developed almost as an afterthought mid-way through his flight trials, was far simpler. It also proved to be the best glider in the world to that date. Planned as a triplane, it was soon converted into a biplane. Like the Katydid, it was a hang glider; its pilot did not fly the craft from an internal position, but hung suspended by his arms and controlled lateral movement by swinging his legs. One of its principal features was a cruciform tail designed to give slightly with the wind.

The testing site was the desolate sand dunes at the southern end of Lake Michigan near Miller, Indiana, thirty miles east of Chicago. Photographs show Chanute on the dunes standing in the pilot’s position beneath his gliders. W. H. Williamson, author of a biographical pamphlet for the dedication of Chanute Field in Illinois in 1940, claimed Chanute made a “few flights” during the trials, his reasoning being that a man of Chanute’s character would never ask other men to do something he would not do first himself. The Chicago Tribune took speculation to an extreme in its obituary of Chanute: “In making 2000 flights long before the Wrights or any of the other heroes of the present day began their experiments, Mr. Chanute escaped without a serious accident.”

That was not much of an accomplishment, since Chanute likely witnessed all those flights from a safe distance. He was sixty-five years old in 1896, and the consensus today is that he never flew in the Indiana dunes or anywhere else, but only posed for a few pictures.

The first set of trials took place in June and July of 1896. Augustus Herring, Chanute’s chief assistant and builder, achieved a best glide of a modest eighty-two feet in the Katydid.

The second trials, in late August and early September, were far more encouraging, the new biplane assuming the leading role. Herring and another young pilot made numerous well-controlled glides over 200 feet, the longest extending 359 feet. During the 2,000 glides that summer—the rough total for all the pilots in attendance—the greatest mishap occurred when Chanute’s son Charles split the seat of his pants. It was a safety record of which Chanute was justly proud.

To flight enthusiasts, it seemed that the age of Darius Green was past. The flight problem was being systematically attacked by trained scientists and engineers, and there was a sense that a major breakthrough was immediately at hand.

That breakthrough never came.

Samuel Langley believed he was only a couple of years from a man-carrying Aerodrome, but he soon discovered that the task was far more complicated than simply scaling-up the design of his model craft. His efforts consumed seven years and vast sums of money. He made his final effort at powered flight the same month the Wright brothers made their historic attempts—December 1903. His venture into aeronautics ultimately brought him the kind of ridicule he’d been wary of from the start, damaging his reputation in the scientific community and his position of public trust as head of the Smithsonian.

Octave Chanute’s interpretation of his glider trials was a mixed bag. On one hand, he understood the flight problem well enough to recognize that neither he nor anyone else was close to developing a powered craft. On the other hand, his further aeronautical research contradicted the evidence he’d seen with his own eyes: he focused on variations of the Katydid, to the neglect of his highly successful biplane. The trials in the Indiana dunes were the high point

of his career in flight.

After the brief promise of 1896, the prospects for flight were as dim as ever.

Unlike many inventions of the Industrial Age, glider construction was not technology-dependent, requiring only inexpensive materials that had been available for centuries. Yet despite a wide variety of experiments, little progress had been made since Leonardo da Vinci.

Though early experimenters were important in laying the groundwork for flight, the fact remains that when the Wright brothers came to Kitty Hawk, they had few positive examples to guide them in a field where defeat was the norm.

The Wrights

There are few points in the story of the Wright brothers that have not been the subject of competing claims and fanciful tales. In some tellings, Wilbur can’t even get off the train and set foot on North Carolina soil for the first time without becoming the subject of rumor.

His trunks packed with the pieces of the brothers’ first man-carrying glider, Wilbur left home in Dayton, Ohio, on Thursday, September 6, 1900, and laid over in Norfolk, Virginia, Friday night. Late Saturday afternoon, he boarded a train for the last overland leg of his journey, which took him through the Dismal Swamp to Elizabeth City.

According to Outer Banks writer Milford Ballance, he happened to find himself sitting across the aisle from a lovely young girl named Nell Cropsey. A little over a year later, “Beautiful Nell” made national headlines when she turned up missing from her home under suspicious circumstances. She was found in the Pasquotank River six weeks later, most likely the victim of murder at the hands of her boyfriend, Jim Wilcox. Nell Cropsey’s murder had a lasting effect on local people, who endured weeks of tension during which the river was dragged and cannons were fired along shore in an effort to shake her body loose from the depths. But it is unlikely in the extreme that her life really intersected Wilbur Wright’s.

Actually, rumors about the Wright brothers in North Carolina go back even farther than that. In 1889, precocious fourteen-year-old farm boy John Maynard Smith of Belhaven, seventy miles southwest of Kitty Hawk, invented a model airplane powered by a clock motor and a tractor propeller—one mounted in front of the wings. Within four years, Smith’s model made it as far as President Grover Cleveland, who, unfortunately, was less than impressed, disparaging the craft on the grounds that “any fool knows that if you put a propeller on the front of a ship, it would push a ship backwards.”

One afternoon in 1897, two strangers stopped unexpectedly at the Smiths’ home and were invited to stay the night. After dinner, the model airplane was brought in from the barn and demonstrated in the living room. The strangers departed early the next morning, stealing the model and John Maynard Smith’s drawings.

Once the Wright brothers achieved powered flight at Kill Devil Hills, some of the citizens of Belhaven thought back to the airplane theft of 1897 and came up with a pair of suspects: agents of the Wrights, or even Wilbur and Orville themselves.

John Maynard Smith and the people of Belhaven had little to worry about from Wilbur and Orville Wright in 1897. To that date, the brothers’ interest in aeronautics had not developed beyond browsing the family bookshelves and the local library. It was the height of the bicycle boom. Just the previous year, the Wrights had graduated from selling and repairing a variety of bicycle makes to custom-building their own line.

When they entered the field, the bicycle was seen as one of the great inventions of the nineteenth century. Bicycles were liberating. They were fast, reliable, exciting, and relatively inexpensive. But the bicycle business was also highly competitive; at one point, there were three other shops within two blocks of the Wrights’ establishment. And the brothers may have sensed that they were partaking of a kind of intermediate technology. Bicycles set travelers free from their dependence on horses, but their potential could not rival that of the automobile. Wilbur was among those who poked fun at the first cars that rattled around Dayton, Ohio, but the future was at hand.

Yet if the Wrights were dissatisfied with what was outwardly a productive life, the real reason was personal. Wilbur in particular had some inkling of his talent, and at age thirty, he was squandering it on a machine already perfected by others. He was a man in search of a great problem to solve.

Wilbur was born near Millville, Indiana, on April 16,1867, Orville in the family’s longtime home at 7 Hawthorn Street in Dayton on August 19, 1871.

Over the years, their personalities have merged in the public consciousness to such an extent that they are often seen as a single entity In Six Great Inventors, for example, author James G. Crowther flatly refuses to draw any distinction between the two: “For the purpose of this book, the Wright brothers have been regarded as one composite inventive personality. Their achievement was the result of mutual inspiration and discussion, and their respective contributions cannot be separated.”

This attitude was sanctioned by Wilbur himself, who once claimed that from the time they were children, he and Orville “lived together, played together, worked together, and, in fact, thought together. We usually owned all of our toys in common, talked over our thoughts and aspirations so that nearly everything that was done in our lives has been the result of conversations, suggestions, and discussions between us.”

But according to Wright biographer Tom Crouch, such a partnership may have been more a conscious decision than a natural development. The Wrights often squabbled during their early business dealings, with one or the other brother feeling he was saddled with an unfair share of the work or was receiving too little credit for his efforts. It was mainly to avoid ill feelings resulting from their work with gliders that they resolved to blur the distinctions between them and present all their ideas as joint conceptions. This attitude grew on them to the point that they even signed their checks “Wright Brothers,” with a simple “W. W.” or “O. W.” the only indication of the signer.

Differences between the two are not difficult to find.

Wilbur was older, balder, and a more avid correspondent. He was the more visionary of the two. As their father, Milton Wright, put it when he learned that Wilbur and Orville had ascended in a balloon together at the height of their fame, “Wilbur ought to keep out of all balloon rides. Success seems to hang on him.” But Wilbur was also prone to depression. One of the defining incidents of his life came in his late teens, when he was inadvertently clubbed in the face while playing a hockey-type game with neighborhood boys. His injuries drove him into a three-year-long withdrawal from friends and family. Aside from the risks he later took in his flight experiments, he seems to have considered himself a kind of invalid-in-waiting from that point. Worn down by lawsuits and stricken with typhoid at age forty-five, he died rather easily.

Orville was probably closer to his younger sister, Katharine, than he was to Wilbur. He was more shy than Wilbur, but also more of a prankster. A dapper dresser, he wore a mustache and had a touch of vanity. Disliking the suntanned look he acquired on the Outer Banks, he would adjourn to the bathroom with a lemon every morning upon getting back to Dayton and set to rubbing his face with its juice, with the result that his skin returned to its normal paleness weeks before Wilbur’s. Though younger than Wilbur, Orville was the leader in their printing and newspaper-publishing ventures before they turned to bicycles.

Building gliders was initially Wilbur’s dream, but some of their breakthrough ideas were Orville’s. And since Orville outlived Wilbur by over thirty-five years, he was the one who stayed in the public’s mind as the patriarch of aviation through the first half of the twentieth century.

It isn’t known exactly why the Wrights took to the flight problem. They experienced no epiphany. Their interest developed slowly over a period of twenty years.

They received their introduction to aeronautics in 1878, when their father, a bishop in the United Brethren Church, bought them a rubber-band-powered helicopter toy during one of his many trips. Designed by French aeronautical pioneer Alphonse Pénaud, such toys could rise to a height of nearly f

ifty feet or hover for almost half a minute. Fascinated, eleven-year-old Wilbur and seven-year-old Orville fashioned successful small-size copies, but failed when they tried to scale-up their design.

When he was in his early teens, Orville built kites and sold them to friends. This short-lived venture was only one of a number of youthful entrepreneurial schemes.

A more important influence came in the great aeronautical year of 1896. Sandwiched between the reports of Samuel Langley’s Aerodrome tests on the Potomac and Octave Chanute’s glides in the Indiana dunes came news that the great German Otto Lilienthal had died in a glider crash.

It is unknown how taken the Wrights were with Langley and Chanute at that date, but like many others of their generation, they had followed news accounts of Lilienthal’s exploits with relish. From 1891 until his death, Lilienthal made about two thousand glides in the Rhinow Mountains north of Berlin in a number of batlike, birdlike, and biplane hang gliders. These glides routinely stretched into the hundreds of feet. He was without question the world’s preeminent glider designer and pilot.

To the many people who pinned their hopes for the future of aeronautics on Lilienthal, his death hit hard. Orville Wright was himself severely ill with typhoid at the time, and Wilbur withheld the news of Lilienthal’s passing until he judged his brother strong enough to take it. The German’s tragic accident got Wilbur thinking seriously about the flight problem for the first time, but in the short term, it didn’t inspire him to do anything more momentous than adjourn to the family library to examine Etienne Jules Marey’s Animal Mechanism, a book covering bird flight that he had already read several times.

His own ambitions took shape slowly over the next two and a half years. By late May 1899, Wilbur was ready for more in-depth information than the public library in Dayton could provide. Sounding like a believer in Octave Chanute’s theory of cooperative experimentation, he wrote Samuel Langley’s Smithsonian for its recommendations on reading material. It was his first communication on the subject of flight:

Scribblers

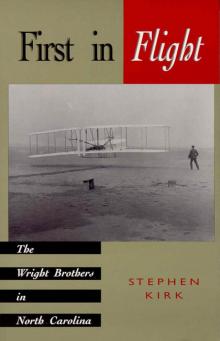

Scribblers First in Flight

First in Flight