- Home

- Stephen Kirk

First in Flight Page 24

First in Flight Read online

Page 24

As for Chanute’s place in the Wrights’ scheme of things, Wilbur wrote this:

I several times said privately that we had taken up the study of aeronautics long before we had any acquaintance with you; that our ideas of control were radically different from yours both before and throughout our acquaintance; that the systems of control which we carried to success were absolutely our own, and had been embodied in a machine and tested before you knew anything about them and before our first meeting with you; … that you built several machines embodying your ideas in 1901 and 1902 which were tested at our camp by Mr. Herring, but that we had never made a flight on any of your machines, nor your men on any of ours, and that in the sense in which the expression was used in France we had never been pupils of yours.

Wilbur tried closing on a hopeful note—“If anything can be done to straighten matters out to the satisfaction of both you and us, we are not only willing, but anxious to do our part”—but he had probably lost his audience long before then.

Three months passed, and Chanute did not respond.

Finally, on April 28, Wilbur sent a conciliatory note: “My brother and I do not form many intimate friendships, and do not lightly give them up…. We prize too highly the friendship which meant so much to us in the years of our early struggles to willingly see it worn away by uncorrected misunderstandings.” He proposed a joint public statement by the brothers and Chanute precisely detailing Chanute’s involvement in their work.

Responding two weeks later, Chanute vowed that, upon returning from an upcoming trip to Europe, he would do his part to try to resume the friendship.

It never happened. Traveling in France with his three daughters, Chanute fell ill and consulted a Paris physician. Told that his heart was failing and that he should sharply curtail his activities, he disregarded the advice and soon found himself in the hospital, where it was discovered he had double pneumonia. His convalescence at the American Hospital in Paris took two months. Back home in Chicago, after showing such signs of improvement that his nurse was dismissed, he died on Thanksgiving Day 1910, at age seventy-eight.

The tribute Wilbur wrote for Aeronautics magazine better reflected his true feelings than his last letters to Chanute:

If [Chanute] had not lived, the entire history of progress in flying would have been other than it has been…. His writings were so lucid as to provide an intelligent understanding of the nature of the problems of flight to a vast number of persons who would probably never have given the matter study otherwise, and not only by published articles, but by personal correspondence and visitation, he inspired and encouraged to the limits of his ability all who were devoted to the work. His private correspondence with experimenters in all parts of the world was of great volume. No one was too humble to receive a share of his time. In patience and goodness of heart he has rarely been surpassed. Few men were more universally respected and loved.

Today, a town in Kansas, a memorial in Gary, Indiana, and an air-force base at Rantoul, Illinois, bear Chanute’s name. The Wright brothers might never have gotten off the ground without his steady encouragement.

Like Chanute a three-time Outer Banks camper, George Spratt was the Wrights’ best friend among the outsiders who came to North Carolina to experiment with them.

They remained in contact after Spratt’s last Outer Banks visit in 1903, the Wrights spending a weekend at his home in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, in 1906 during a sojourn from their first effort at selling an airplane.

Unfortunately, the friendship followed the same course as the brothers’ relationship with Chanute.

The point of contention with Spratt was a measuring apparatus the Wrights used in the wind tunnel they built after the 1901 season. Where other experimenters had designed separate tests to determine the lift and drag of wing sections, Spratt told the Wrights of a way to measure the ratio of lift to drag in a single test. The Wrights’ wind-tunnel tests constituted some of the most important work they ever did, and Spratt’s tip was vital to unlocking the secrets of wing design.

Spratt was repaid, appropriately enough, with the complete data tables from the brothers’ wind-tunnel experiments, which were far more accurate than anything the Pennsylvanian had arrived at himself. But once the Wrights achieved world fame, that somehow wasn’t enough. Spratt wrote them in 1909 complaining that he had never been given proper credit for his contribution. Aside from Spratt’s participation in some of the Wrights’ legal proceedings, the relationship was effectively ended.

In 1922, when Orville was thinking of authoring a personal account of the development of the airplane, he reestablished contact, writing Spratt to ask him for copies of letters the Wrights had sent him in the early days. Spratt declined, and went on to lay into Orville for what he considered the Wrights’ secretiveness and their general obstruction of the progress of aviation.

“Not wishing to add to the sorrow of an already unhappy life,” Orville wrote to a friend after receiving Spratt’s letter, “I have refrained from making any reply.”

“He doesn’t want those letters just to make photostats,” Spratt told a reporter for the Coatesville Record, his hometown paper. “What he wants is to get his hands on those letters, and if I send them to him I’ll never get them back.”

Meanwhile, Spratt was busy developing his own design ideas, his work proceeding at the kind of pace that had doomed many experimenters to failure before the Wright brothers came on the scene.

An advocate of parabolically curved wings early in his career, Spratt later switched camps and began touting wings with a circular curve, which he now believed would lend greater stability in the air. Having spent his early days in aeronautical study removing the tail feathers from live birds and seeing how they flew without them, Spratt had another pet notion: a tailless airplane. He envisioned what he called a “controllable wing” craft. It would have no ailerons or wing-warping system and either a small, fixed tail or no tail at all; its wings—featuring a circular curve and mounted on a universal joint, so they could tilt forward, backward, and from side to side—would assume all conventional aileron and tail functions.

The goal, as it developed over the years, was an inexpensive craft that would be stable at low speeds. Since it was to be operated by a single control, roughly analogous to the steering wheel of a car, flying it would require virtually no training.

In those days, with the future course of aeronautics a matter for speculation, some observers believed that every American home would eventually have an airplane in the garage, right beside the automobile. George Spratt was one of the men who hoped to open aviation to the masses.

His first step was a “controllable wing” biplane glider, built in 1908. Spratt flew the craft himself, towed into the air alternately by an automobile and a horse.

The next step, though exceedingly slow in coming, brought Spratt the greatest attention he ever received. In 1934, he introduced a powered “controllable wing” biplane. The craft flew under its own power to much local fanfare in early October, the inventor’s son, George G. Spratt, at the controls. It was a selling point that the younger Spratt, entirely untrained to fly conventional airplanes, could pilot his father’s craft with minimal practice.

Newsreel photographers came to Pennsylvania in 1934 and 1935 to record the tests; a reporter for the New York Times came, too. The 1935 newsreel photographer captured the airplane taking off and flying. He also recorded it in its “roadable” mode, driving happily down a conventional roadway powered by its propeller, its wings rotated to run along the length of its body from front to back, rather than from side to side in flying position.

In mid-November, it was demonstrated that the airplane could fly backward as well as forward. “The only changes that were made in the structure of the ship to make it fly backwards were to turn the seat around so that the pilot could see where he was going, to replace the tractor propeller with a pusher type and to put the tail on the front end,” the Coatesville Record reported.<

br />

George Spratt lived just long enough to see his airplane in newsreels at a local theater. His health was always poor. He endured numerous hospital stays over the years, and he supposedly witnessed one of the first trials of 1934 from a stretcher. Never having made a dime off his forty years in aeronautics, he lived his last years in a small room at the Coatesville YMCA. He died of heart failure at his son’s home in late November 1934, at age sixty-five.

George G. Spratt continued his father’s work. In 1945, he developed a “controllable wing” airplane for the Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Corporation. Nicknamed the Doodle-Bug, it looked more than a little like a Volkswagen Beetle with a wing on top. Strangely enough, the craft was built and tested in and around Elizabeth City, North Carolina, just up Albemarle Sound from where Spratt’s father had camped with the Wright brothers.

Of course, those were the days when the Nazi war machine, heading toward its last days, was making revolutionary breakthroughs with jet aircraft. A new era of aviation was set to begin. The future did not rest upon craft designed for slow speeds and pilots with minimal training, but upon high-performance planes flown by specialists. The Spratt airplanes were interesting, but they didn’t make a major contribution to the progress of the science.

When the 1903 Wright Flyer was brought to the Smithsonian from England after World War II, George G. Spratt was one of the guests at the ceremony.

Spratt, age ninety, was still making occasional news as of January 1995, when Air and Space Smithsonian carried an article on his and other designers’ efforts at popularizing “controllable wing” airplanes. At that time, he was a living testament to the ease of operating such craft, having logged hundreds of hours without ever acquiring a pilot’s license or even taking a single flying lesson.

As for Edward Huffaker, George Spratt’s fellow camper in 1901, he dropped out of aeronautics for a decade and a half upon returning home from the Outer Banks. With his wife dead and two children to raise, he took up his old career as a surveyor for a means of support. He also served for a time as postmaster of Chuckey City, Tennessee.

His interest in flight was rekindled upon being called to testify in behalf of Glenn Curtiss in the Wright brothers’ patent suit against Curtiss. Back home in Tennessee, Huffaker started building and testing model airplanes as in the old days, his goal being to design an inherently stable craft. These efforts culminated in 1920, when he was issued a patent for a new stabilizing device. However, he never managed to interest manufacturers in his invention.

In 1930, Huffaker moved to Oxford, Mississippi, to be with his daughter, Mary Ada, wife of the chancellor of the University of Mississippi. A teacher like her late mother, Mary Ada supposedly gave music lessons to William Faulkner’s children in their home.

When he wasn’t taking long walks around campus, Edward Huffaker was a familiar figure at the university library, where he is said to have read the entire collection of books in Greek and Latin. He also continued his interest in airplane design, contacting his former employer, the Smithsonian, about the possibility of securing grant money to develop a “flying wing.”

Edward Huffaker died in 1937, at age eighty-one.

To all appearances, Augustus Herring, a camper on the Outer Banks in 1902, was a talented man who ran out of ideas early, then tried to hang onto his position in the aeronautical establishment by any means he could, to the point of becoming a general nuisance.

When Herring left the Wrights’ camp, he headed to Washington with a view to exchanging information on the brothers’ work for a job at the Smithsonian.

The following year, he moved from St. Joseph, Michigan, to Freeport, Long Island, his wife’s home territory, where he lived the rest of his life.

The 1902 season on the Outer Banks didn’t end the Wrights’ dealings with Herring. In late December 1903, about a week after arriving home following their historic flights, they received a letter from Herring proposing they form a three-way business partnership. According to Herring, he had already received feelers about selling his rights in future patent suits against the brothers. Bringing Herring on board might thus serve as a hedge against litigation. The Wrights didn’t bite.

Then, after the United States government issued a bid for a powered, heavier-than-air flying machine in December 1907—a bid tailored to the Wrights but open to all comers—Herring stepped forward with a proposal. Most observers doubted he even had an airplane, much less one that could fulfill the government’s strict requirements. Herring’s supporters claim he did in fact have a craft in the works—a light biplane with twin five-cylinder engines—and that he later tested it at a field near his home, at which time it crashed and was destroyed.

In early 1909, Herring approached Glenn Curtiss with the same kind of partnership offer he had tendered the Wrights. Claiming he had patents that predated and invalidated the Wrights’, he assured Curtiss that a jointly held company could not be successfully sued for infringement. The Herring-Curtiss Company soon became a major force in the aeronautical industry. However, with Glenn Curtiss the principal designer, Herring still found himself in the background.

When the Wright brothers brought suit against the Herring-Curtiss Company, Curtiss quickly learned that his partner had no patents at all. He dissolved the partnership to free himself from Herring, upon which Herring turned around and sued Curtiss for illegally kicking him out of the company. This monumentally long suit lasted until 1932, after both men were dead. Curtiss’s widow ultimately agreed to pay a settlement of half a million dollars. After legal and administrative fees were siphoned off, thirty thousand dollars filtered down to Herring’s heirs.

In February 1910, when the Herring-Curtiss partnership was about to reach the boiling point, Herring did achieve one last, if minor, aeronautical triumph. Backed by W. Starling Burgess, a yacht designer, he built and flew a biplane off Chebacco Lake in Essex, Massachusetts. His supporters claim it was the first powered flight in New England, though it lasted only five seconds and covered just forty yards—little better than what he had accomplished on the shore of Lake Michigan nearly twelve years earlier.

Soon afterwards, Herring suffered the first in a series of paralytic strokes. Despite his health problems, he was able to do a little engineering consulting and to continue participation in his lawsuits. He died in 1926.

His son, Bill, was a major-league pitcher for the New York Giants.

Augustus Herring never conceded the Wright brothers the high ground, summing up his opinion on the birth of flight in one memorably pithy comment during court testimony: “The airplane had a good many daddies.”

The fortunes of radio experimenter Reginald Fessenden continued their rise and fall.

Unlike the Wright brothers, who became famous almost instantly upon going public with their invention, Fessenden reaped little reward when he made the first two-way Morse transmission across the Atlantic, when he became the first to send voice across the ocean, and when he made the world’s first radio broadcast. In fact, his new employer, the National Electric Signaling Company, required that he sign over all the patents he developed during his tenure, so he didn’t even have the rights to some of his greatest radio inventions. After much in-fighting, he was squeezed entirely out of the company shortly after Christmas 1910. As during his tenure with the Weather Bureau, his employment came to an ugly end, an officer of the court serving him legal notice forbidding him to have further dealings with the company.

A couple of lean years followed. Without steady employment, Fessenden took to gimmickry, inventing things like aluminum bags to hold tea and violins with built-in amplifiers. He and his family lived in cheap rooming houses and gradually sold off their possessions to pay for food, rent, and legal fees for Fessenden’s never-ending patent suits. It was during this hard-luck period that Fessenden approached Orville Wright about the prospect of building an airplane motor.

Things picked up in the middle of 1912, in the wake of the greatest tragedy of the time: the sinking o

f the Titanic. Fessenden was standing in a train station in Boston when he bumped into an old friend who worked for the Submarine Signal Company. The friend inquired as to whether radio waves might be used for communication between submarines, and whether they might have some use for locating icebergs and dangerous rocks. A new door open to him, Fessenden went back to serious work, eventually producing a pair of noteworthy breakthroughs: the sonic depth-finder, or fathometer, and elementary sonar.

The outbreak of World War I led him to one of his most productive periods. One of his first war proposals had to do with airplanes. At a time when factories were building only a few dozen planes a month, he came forward with plans for a Canadian plant that would produce them like Henry Ford produced automobiles—two hundred a day, for the purpose of dropping bombs on the enemy. Of course, training pilots to keep up with such a pace was another matter entirely, and the plant never came to pass.

Other ideas were better. Back in 1908, Fessenden had invented the turbo-electric drive, which was later used to power battleships and other vessels. Now, he put his radio waves to use in designing wireless communication systems between artillery batteries and in devising a means to locate enemy zeppelins in the air. He also invented the tracer bullet. When poison gas was used on Canadian forces, it was Fessenden who came up with the idea of igniting petroleum in front of the trenches, which caused the gas to rise out of harm’s way on the heated air.

Scribblers

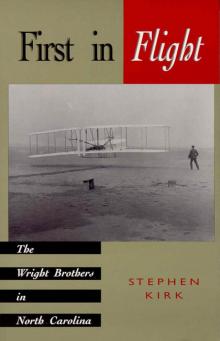

Scribblers First in Flight

First in Flight